In 1991, Brain Mulroney and George Bush signed the acid rain accord, putting into place policies that to this day ensure that acid rain is no longer a major problem in Canada or the United States. Today, Canadians seldom even consider the issue of acid rain, seeing it as largely resolved.

Addressing environmental issues, like acid rain, typically follow a similar pattern as first observed by Tony Downs, in 1972. First, no one is paying attention to an environmental issue. Then something happens to put it on the public’s radar. This leads to widespread support for action, which is when the public realizes the costs associated with interventions. This leads to debate and eventually for public interest to decline. Finally, the public moves on to other concerns.

Recognizing this pattern, the key to addressing environmental problems is putting actions in place when the public is supportive. Those actions will then continue to work after the public has lost interest in the issue. The restrictions on pollution in the acid rain accord are a perfect example, as they continue to apply today despite the public’s lack of interest in acid rain.

Research in the latest issue of the Canadian Political Science Review, published by myself and my former Conestoga College students (Natalie Pikulski, Pranol Kunjamon Mathan, Suhani Singh, and Sarah Strickland), demonstrates that Canada missed an opportunity to act on climate change in 2007.

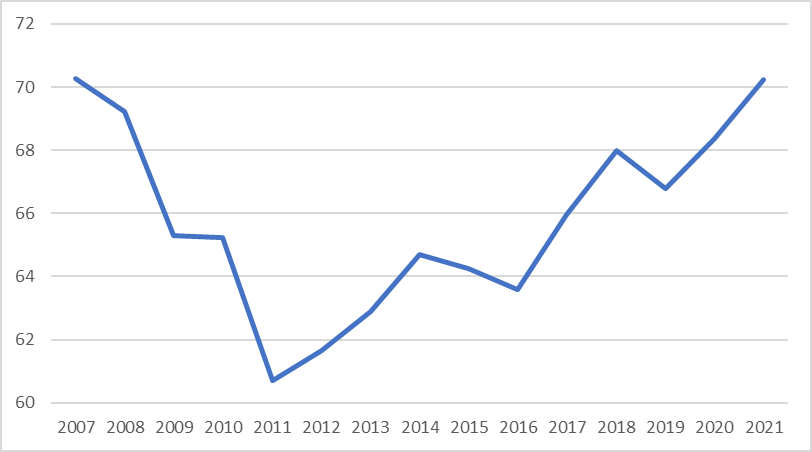

Our study used an algorithm to combine 29 different surveys from five Canadian polling firms between 2007 and 2021 to create a Belief in Climate Change Index. Individual polling firms estimate belief in climate change was as low as 52% to as high as 91%. Since polling firms ask different questions in different ways with different response options the index is best used as a trend line and not as an indication of the percentage of the population that believes in climate change at any moment in time.

When examining the trend line, belief in climate change starts at a peak in 2007, then dropped to the lowest point in 2011, before steadily rising back to a peak today in 2021. In 2007, there was a clear opportunity to address climate change with high public interest in the topic.

In the 2000s, some action was taken in response to public support, most notably the closing of coal-fired plants in Ontario. Closing coal plants combined with the financial crisis led to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in Canada from 2007 to 2009. Yet, rates then began to rise again.

Today, public belief in climate change is once again at its highest level since 2007 suggesting an opportunity for action once again exists. The most recent poll on this topic, done by Forum Research during the federal election, echoes this finding as it showed that 85% of respondents who had an opinion believed that climate change is caused by human activity. This is the highest level reported in a Forum Poll asking this question.

With a minority parliament, the breakdown of who believes in climate change is particularly relevant, as it shows which parties may be most likely to support action. The Forum Poll shows that 97% of Liberal Party and New Democratic Party supporters and over 87% of Green Party and Bloc voters also believe in climate change. Indicating that the Liberals have multiple potential partners to pass legislation related to climate change. (Belief amongst Conservative Party supporters is 75% but only 49% amongst People’s Party of Canada supporters).

A window of opportunity has opened for actions on climate change in Canada. Any actions taken should be designed in a way that they will continue to operate after the public has shifted attention to other issues. Policies should therefore be locked in and predictable. Policies developed today should make clear where they will be in ten years. This can look like a carbon tax with phased-in annual increases, industry energy efficiency standards phased in over a decade, and timelines for when vehicles with fossil fuels will be banned. Failure to act effectively will only lead to climate change returning to the public radar in a few years. Unfortunately, given the risk to the planet by then, it may be too late to prevent serious harm to the planet.