By Sarah Stickland

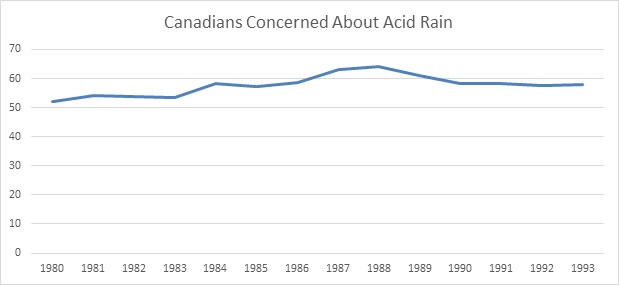

In the previous blog, I explained that acid rain was in the pre-problem stage in the 1960s and that the public became concerned about acid rain in the 1980s. This blog post will go over the policies the federal government implemented to reduce acid rain and an example of an industry implementing change.

In the 1970s the government implemented policy’s to reduce acid rain as a means to improve the air quality. The federal government created reduction targets. By the late 1970s the federal government worked with the provinces to create a reduction plan. The reduction plan in 1983 was to reduce the about of sulphates in precipitation to less than 20 kg per hectare per year. Reference. The Federal government, under Prime Minister Mulroney, instituted the Canadian Acid Rain Control Program in 1985. The Canadian Acid Rain Control Program had three mandates: set targets and schedules to reduce emissions, develop new technologies to reduce emissions, and research and monitor emissions. Reference. However, the industry were ahead of the government with technological advancements in the 1960s. Industries were reducing concentration of sulphur that went into the processing to lower the cost of production (Buhr 1998). Coincidently, there was an environmental benefit occurring at the same time, acid rain was slowing becoming resolved. The public acknowledged that there was a correlation between the industry reducing sulphur in production and reduction of acid rain. Industry’s continued to meet government reduction targets because it looked good for public image.

Figure 2: Canadian Sulphur Dioxide Emission (Source Canadian Government Report)

An example of an industry making changes is Falconbridge. Falconbridge is a smelting company in Sudbury, Ontario. Falconbridge created the Smelter Environmental Improvement Project to reduce sulphur in processing. One of the methods Falconbridge tried was a nickel-iron refinery and a pyrrhotite treatment plant, however it was unsuccessful because of economic reasons (Buhr 1998). Falconbridge was successful at maintaining below government regulations on sulphur dioxide per year.

Therefore, policymakers can control the public’s attitude about an issue. This is evident with the case of acid rain in Canada. Acid rain was problem long before the publics was focused on resolving the issue. The public entered the euphoric stage in the issue attention cycle after the federal government began implementing regulations to reduce emissions. Acid rain was resolved in the 1990s because the public become concerned and the demonstrated that it was an issue that the government needed to focus on through public opinion polls. In other words, acid rain successfully went through the attention issue cycle without the public getting discouraged. The trend of the public concern for environmental policy continues into the 1990s with the case of ozone depletion.